Protection in Operating Systems

Operating Systems are the backbone of the computing devices, as they are the link between hardware and software; every computer runs them, and their understanding is fundamental for understanding Cybersecurity.

In this note we will look at how operating systems ensure protection across its system, specifically how it ensures the following two properties:

Protection

When we talk about protection in operating systems, it is important to ask this question:

What are we protecting, and from who?

To answer this question, it is fundamental to understand how operating systems work, namely in the following two aspects:

- Computers contain resources called objects, such as:

- CPU

- Memory pages, memory devices

- I/O devices (disks, printers, network, etc.)

- Dynamic Libraries (DLLs)

- Objects are accessed by subjects:

- Can be users, groups, processes

With these two definitions, we can now answer the question above: we need to ensure that objects are not accessed by unauthorized subjects.

To implement this, we need to guarantee two properties: separation, which prevents arbitrary access to objects, and mediation, that dictates who has access to what (access control).

Separation

Modern operating systems can run software in basically two modes:

- Kernel Mode: Software can access any object

- User Mode: Access control is controlled by OS

There are more execution modes (e.g. hypervisor mode), but this is irrelevant for this topic

These modes are enforced by the CPU; this simply means that the CPU, running in user mode, will simply disable some of its instructions, like in/out, sti/cli, hlt, and more. To disable means to either generate exception or do nothing (depends on the instruction).

This means that in order to perform certain actions, processes in user mode will have to ask OS Kernel to do those actions/operations. For this, user can make use of system calls:

- System Calls: operations that resemble functions, but they are done in the OS and are reserved to the kernel

- Control the access of from user mode objects to all other objects outside their memory

This presents two difficulties, namely:

- OS kernel runs in kernel mode, not user mode (how to make the transition?)

- The kernel memory space is invisible to the user process

The solution for this "gap" between user mode and kernel mode is the usage of software interruptions (in x86, triggered by int instruction). This allows for user processes to seamlessly request OS to perform kernel mode operations.

Memory Protection

One of the most important forms of protection/separation is memory protection; this is ensuring that processes running in user mode cannot change memory from other processes or the kernel memory.

Forms of Separation

There are four different types of separation that an OS uses to ensure separation (as a whole, not only memory separation):

- Physical Separation: different processes use different devices (e.g. a different printer for each level of security)

- Temporal Separation: processes with different security requirements are executed in different times

- Logical Separation: processes operate under the illusion that they are the only process in the system

- Cryptographic Separation: cryptographically protect certain parts of the memory, to be unintelligible to other processes

Separation for Memory Protection: Logical Separation

The most important and widely used method of separation for memory protection is logical separation, i.e. make the processes work under the illusion that they are the only processes in the system. To implement this there are several solutions, but the most common are:

- Segmentation

- Paging

- Segmentation + Paging

Segmentation

With segmentation, a program is split into parts (code, data, stack), and then memory is divided according to the size of these parts, called segments (segments are therefore variable in size).

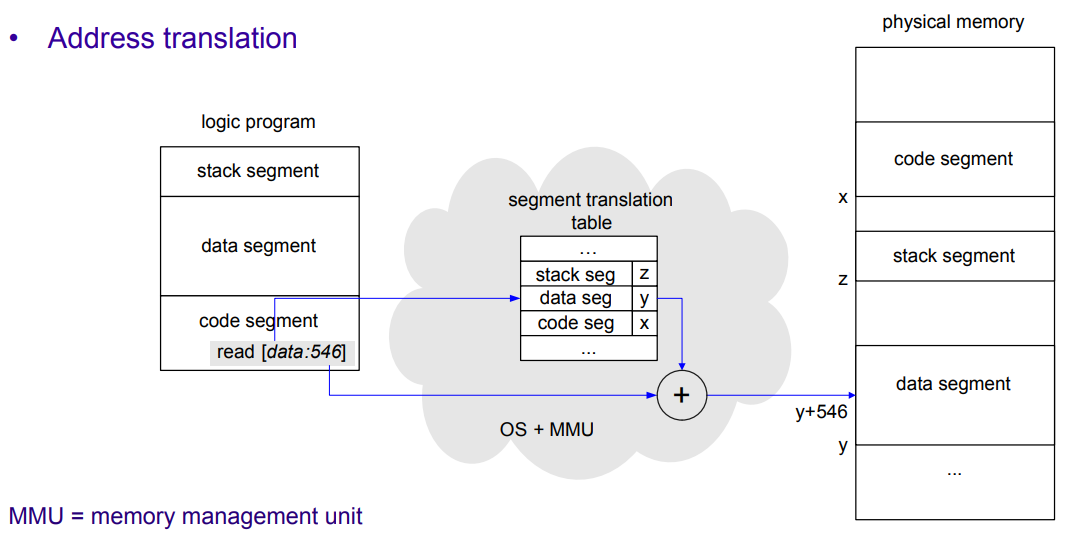

To keep information about segments and respective owners, the OS keeps a segment translation table for each process, that keeps records of the beginning of segments. These tables ensure separation, as processes can only "see" segments that are in their segment translation table; furthermore, when a process tries to access a segment, the OS will perform access rights checking (to prevent, for example, the data segment from being executed). In Fig.1 (image below) we can see an example of a segment translation table.

However, there are some problems to segmentation, namely:

- Originates fragmentation in the memory

- Checking the end of a segment is expensive

Fig.1: Address translation in segmentation

Paging

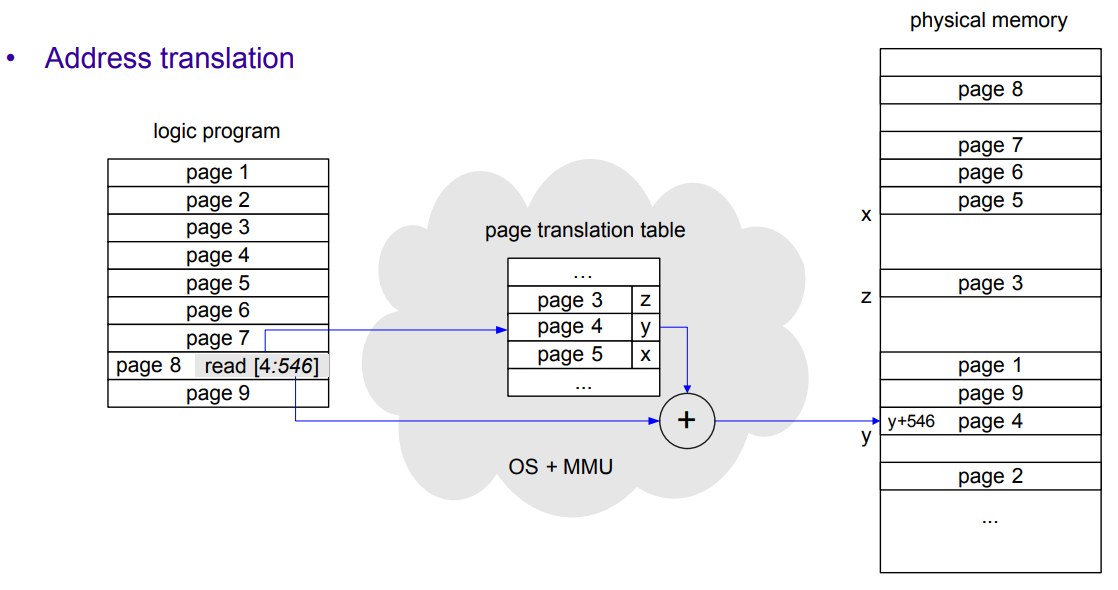

In contrast to segmentation, paging divides the memory into fixed size blocks called pages (typically 4KB). Similarly to segments, each process has its page translation table, in which memory is addressed by (page, offset); fig.2 (image below) shows an example of this.

With paging, we keep the protection characteristics of segments (processes only see pages in their page translation table, access rights checking in every access), but remove external fragmentation (we instead have internal fragmentation).

Fig.2: Address translation in paging

Segmentation + Paging

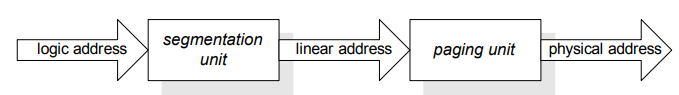

It is possible to create an architecture that merges these two mechanisms; Linux on x86 CPUs does this. The program works with logic addresses (correspond to segments) which are then converted to linear addresses (addresses of the virtual memory, correspond to pages), which are then converted to physical addresses. In fig.3 (image below) we can see a schematic of this translation mechanism.

Fig.3: Address translation in segmentation + paging ^578629

To ensure access rights checking in this type of memory separation, the CS register in the CPU will contain the Current Privilege Level (CPL), which in Linux can take two values:

- 0 - Kernel Mode

- 3 - User Mode

For access rights checking in segments, Linux keeps a Global Descriptor Table (GDT), which contains entries for segments. In these entries it is stored the Descriptor Privilege Level (DPL). In every access, the OS will do the following check: CPL <= DPL. Therefore, the lower the DPL the more private it is; for example, entries with DPL = 0 can only be accessed in kernel mode (segments that are part of the OS, for example).

For page accessing, each page keeps two flags:

- Read/Write flag: States whether you can read or write to this page

- User/Supervisor mode: In supervisor mode pages can only be accessed by CPU in kernel mode

Mediation

In the previous chapter we saw how OSs ensure the separation of objects, so that no leaks of information can happen by arbitrary accesses. We also talked about access control; in this chapter, we will see how that access control is enforced.

Access control is concerned with mediating the access of subjects to objects. This access control should be implemented under a reference monitor; this reference monitor has the following three properties:

- Completeness: it must be impossible to bypass

- Isolation: it must be tamperproof

- Verifiability: it must be shown to be properly implemented

In practice, this reference monitor is scattered across the kernel.

Access Control Mechanisms

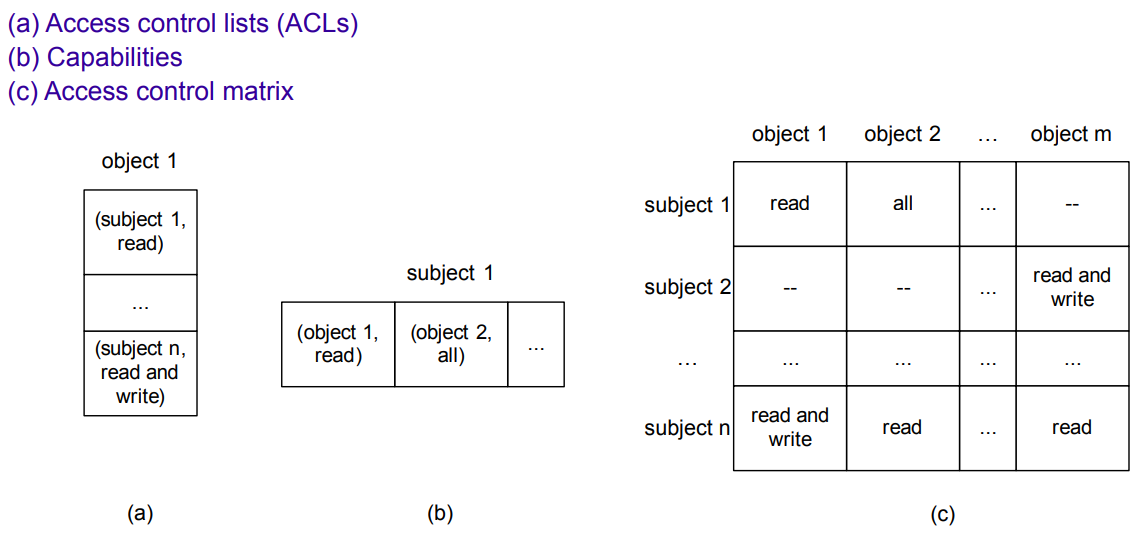

In this chapter we will depict the three main access control mechanisms that exist:

- Access Control Lists (ACLs)

- Each object has a list

- Each list contains the pair (subject, rights)

- Capabilities

- Each subject as a list of rights to access objects

- Each list contains the pair (object, rights)

- Cryptographically protected against forging and tampering

- Access Control Matrix

- Lines for subjects, columns for objects, rights in the cells

In the following image we can see an illustration of these mechanisms:

Fig.4: Access Control Mechanisms illustration ^c3def8

But who defines the rights to access objects? Usually, the owner of each object defines who can access each of its objects. In the case of special operations (add/remove users, network services, etc.), modern OSs define a special user (superuser or root in Linux, Administrator in Windows), that has access to (almost) all of these special operations.

Unix Access Control Mechanism

In Unix, each user has an username associated with it, and additionally two types of IDs:

- User ID (UID): each user has a unique user ID; root user corresponds to user ID 0

- Group ID (GID): the user has a group ID for each group that it belongs to

Additionally, each object (file, directory, device) keeps stored the owner's UID and GID, and the read, write and execute permissions for the following identities:

- Owner

- Group

- World (other users not in the first two)

One important thing to note is that, in Unix, objects are not accessed by users, but instead by processes. How is access control enforced then? Processes have associated with them two IDs:

- Effective User ID (EUID)

- Effective Group ID (EGID)

These IDs are the ones being compared and checked with the object's permissions. But what values do they take? Usually the UID and GID of the user that called the process, but there are exceptions to this: imagine a user want to change its own password. To do that, it will have to call the program setpasswd, but setpasswd must be run as root (for obvious reasons). How can a normal user call programs that require root? The solution is an additional two access bits:

- setuid

- setgid

setpasswd has setuid root, which means that the calling process of setpasswd (which initially has EUID = user ID) will temporarily escalate the EUID to be equal to 0, allowing it to call setpasswd.

setuid and setgid are therefore vital for running root programs in Linux as a normal user. However, they do violate the following principle:

Every program and user should operate with the least possible privileges in order to complete their respective tasks

There are some strategies to mitigate this violation of the principle, such as:

- Execute privileged operations in the beginning, then reduce privileges using seteuid or setegid

- Divide the software in components, and run the least amount of components with higher permissions

- Use chroot() to change the root directory, which only allows the user to modify files under that new root

- Use Linux capabilities

Linux Capabilities

Linux also has a more fine-grained way of allowing processes to execute certain root actions, without changing EUID; Linux calls this capabilities (Attention: not the same as the capabilities mentioned in this section).

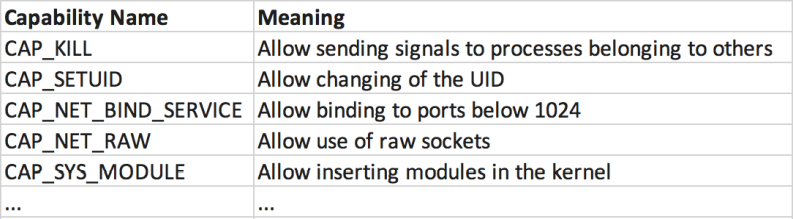

These are some capabilities that processes can run with:

Fig.5: Some of Linux Capabilities

Mandatory vs Discretionary Access Control

We have seen how access control works in Unix, but the question still remains: who can define what does each subject have access to? There are two ways of answering this:

- Discretionary Access Control (DAC)

- Defined by each user

- It is the one used in Linux

- Mandatory Access Control (MAC)

- Defined by an admin

- Linux Capabilities allow to do MAC in Linux